The Holy Martyrs and Confessors Theodora, Evdokia, Maria, and Justina of Borovsk

Commemorated November 2/15

The link for the Usov book “The Church of Christ Temporarily Without a Bishop” is here, with some excerpts:

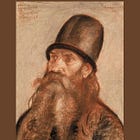

Today is the commemoration of some of the most ubiquitous martyrs of the Old Believer Schism, the Boyarina Morozova and others, whose tale inspired countless retellings and the famous Surikov painting below, which has a nice explanation here.

The hagiographic source we shall rely on for this account, and from which we will occasionally quote, is a manuscript from the late 17th century housed in the Russian National Library (Q.I.341.L.1-58 verso). It bears the title: "On the Second Day of the Month of November: A Narrative, in Part, of the Valor and Courage, the Noble Witness, and the Patient Suffering of the Newly Revealed Holy Great-Martyr Theodosia Prokopyevna, Known in Monasticism as Theodora, Named After the Earthly Glory of the Morozov Family, and of Her Only Sister and Fellow-Sufferer, the Pious Princess Evdokia, and Their Third Companion, Maria."

The original text of the "Narrative" has not been preserved in its entirety. It survives in three redactions: the Detailed, the Abridged, and the Brief, as classified by A.I. Mazunin, who first undertook a scholarly publication of the text in 1979. The earliest and most complete redaction is the Detailed, which most closely reproduces the lost authorial text, composed between 1675 and 1677. Shortly thereafter, the so-called Abridged redaction was compiled, omitting references to certain individuals and events included in the original. Finally, in the Vyg Monastery in the 1730s, the Brief redaction was created, adorned with rhetorical embellishments and syllabic verses that had by then become widely used.

The Lives of Theodosia and Evdokia

Theodosia and Evdokia, two sisters by birth, were the daughters of Prokopy Sokolnin, a wealthy official serving on the Tsar's council, and his wife Anisia. When Theodosia reached the age of 17 (in 1649), her parents arranged her marriage to the nobleman Gleb Ivanovich Morozov (who passed away in 1662). The couple had a son, Ivan Glebovich, born in 1650. Theodosia was spiritually guided by Archpriest Avvakum, later martyred for his faith. News of the renowned widow’s loyalty to the Old Faith reached the Tsar, resulting, as the "Narrative" recounts, in the confiscation of half of the Morozov estates.

Relatives who had accepted Patriarch Nikon's reforms attempted to persuade her to align with the authorities, invoking her maternal duty to her son Ivan. To this, the blessed one replied: "I will not fulfill your will, for I love Christ more than my son. And know also that if I persevere to the end in the faith of Christ and am granted to die for it, none shall take Ivan from me."

Through the prayers of God's servant Theodosia, her younger sister, Evdokia, wife of Prince Peter Semenovich Urusov, was inflamed with the same zeal for God. Eventually, Theodosia began to consider monastic life. She sought the counsel of the elder Melania, whom she greatly revered, and asked for tonsure, which was soon carried out with the assistance of the hieromonk Dosifey, who had recently arrived from the Don. At Melania's request, Dosifey secretly tonsured Theodosia Prokopyevna Morozova as a nun, giving her the monastic name Theodora. The newly tonsured nun hastened to entrust her boyar and household affairs to those she trusted, dedicating herself with redoubled and tripled fervor to greater ascetic labors: fasting, prayer, and silence.

The boyar residence—now transformed into Theodora’s monastic hermitage—became a haven for the Old Orthodox Eucharistic assembly, a "domestic church," and a "forge" of new confessors of the Old Piety. Among these were Elena Khrushcheva, mentioned in the letters of Archpriest Avvakum, and Maria Danilova, wife of the musketeer captain Joakim Danilov, who would later join Theodora and Evdokia in their sufferings. It happened once that Hieromonk Dosifey administered communion to Theodora, Eudokia, and Maria, and with spiritual eyes beheld their faces shining "like angels of God." He understood and said: "This is no ordinary thing; I think that this year they will suffer for Christ," which soon came to pass.

Meanwhile, in January 1671, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich married the young Natalia Kirillovna Naryshkina, the future mother of Peter I. According to court etiquette, the foremost boyars were required to participate in the Tsar’s wedding ceremony, and Theodora was expected to proclaim the Tsar’s name and titles: "Blessed…," kiss his hand, and receive the blessing of the apostate bishops. But the nun-confessor would not attend the ceremony. When the Tsar’s envoys came to summon her, she complained of weakness in her legs, claiming she could neither walk nor stand.

Sooner or later, such a confrontation was inevitable; finally, the time had come for her to "stand courageously to the end," for "Blessed is the man that walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly." The "counsel" soon gathered. The Tsar, angered, declared: "It is hard for her to contend with me—one of us shall surely prevail!" On the eve of the Nativity Fast, Theodora dismissed all her guests, saying: "My dear mothers! Go each of you where the Lord shall preserve you. Bless me for the work of God, and pray for me, that the Lord may strengthen me by your prayers to suffer without doubt for His Name."

Shortly thereafter, Evdokia Urusova departed. At home, sitting at the dinner table, Prince Peter Urusov recounted to his wife the Tsar’s council and concluded his story with the Lord’s words from the Gospel: "Fear not them which kill the body, but are not able to kill the soul." Evdokia received these words with joy and asked her husband’s permission to return to Theodora’s house. Once there, she never left her sister’s side.

When the Tsar’s envoys came to the house, Theodora and Evdokia were ordered, as a preliminary measure, to move from the upper chambers of the boyar residence to the ground floor servant quarters. Theodora’s son, Ivan, accompanied his mother down the stairs, and, seeing her off, bowed to her in the courtyard before returning to the manor. This marked the beginning of the holy martyrs’ imprisonment, which would end only with their departure to eternal rest in Christ.

Soon after, the two women, still refusing to walk "the path of the ungodly," were brought to the assembly hall of the Chudov Monastery, where Metropolitan Pavel of Krutitsy—a zealous supporter of Nikon’s reforms and one of the organizers of the Council of 1666–1667—awaited them along with other "officials." There, they were subjected to interrogation about their faith—first the nun, then the princess. The Metropolitan admonished Theodora, appealing to her conscience as a mother and invoking her young son. Yet she replied: "I live for Christ, not for my son." The princess was then brought in, but the Metropolitan failed to sway her as well.

Following this interrogation, long chains were placed upon the martyrs, with heavy wooden blocks attached to one end and iron collars to the other. Seeing the chains, Theodora made the sign of the Cross over herself and kissed the collar, praising God for granting her "the bonds of Paul." Bound with chains and carrying the blocks, she was placed on a sleigh and transported to the "investigation chambers" at the Pskovo-Pechersky Monastery compound in Bely Gorod (near the present-day Smolenskaya Square in Moscow). According to the "Narrative," they passed through gates beneath the "Tsar’s walkways," likely referring to the then-called Iversky (later Voskresensky) gates of the Kitai-Gorod fortress wall.

Knowing that the Tsar was observing from the gate gallery as she was "transported," Theodora folded her fingers in the two-fingered sign of the Cross, raised her hand high, and "frequently blessed herself with the Cross, while also often clinking her chains." The Tsar saw that the boyar widow Morozova was not only unashamed of her "stubbornness" but rather "greatly delighted in the love of Christ and rejoiced in her bonds." This moment became the inspiration for Russian artist Vasily Surikov’s renowned painting Boyarynya Morozova.

As for Princess Evdokia Urusova, she was similarly bound with chains and blocks and taken to the Alekseyevsky Convent in Chertolye "under strict supervision." There, the authorities attempted to forcibly "lead her into the church," but she resisted, lying down on the ground and refusing to move, much to the irritation of the nuns, who often beat her for her obstinacy.

Another resident of the Morozov household, Maria Gerasimovna Danilova, the wife of the musketeer captain Ioakinf Ivanovich Danilov, fled to the Don when the persecution of this household church intensified. However, she was detained there due to an informant's denunciation and brought back to Moscow. When questioned about the dogmas of her faith, she praised the Orthodox faith and refused to accept the innovations of the Patriarch and Tsar. For this, she too was shackled in chains.

Meanwhile, the authorities increased their scrutiny over those close to Boyarynya Morozova. Her son, Ivan Glebovich, was ordered to be kept under special care. It is difficult to say how attentive or benevolent this care truly was, but the boy, after bidding farewell to his mother, fell ill and was bedridden. Physicians were summoned, but as the Narrative recounts, they so overtreated him that he passed away.

A Nikonian priest was sent to inform the mother of her son’s death. Shamelessly, he applied to her the words of Psalm 108: "Let his house be desolate, and let no one dwell in it; let his children be fatherless," and so forth—claiming that her disobedience to "the truth" brought upon her a curse from God. The suffering mother paid no heed to the priest's "blasphemy" but fell before the icon of the Savior and wept for her son, "chanting funeral hymns," possibly laments, with such grief that it was impossible for anyone who heard her not to weep alongside her.

That year, Mother Theodora, while "in chains and under strict guard," was granted the great blessing of receiving the Holy and Divine Mysteries from the hand of the venerable Job of Lgov. The guards, remarkably reverent, allowed the elder hieromonk to enter and minister to the suffering saint, after which he departed peacefully.

The death of Ivan Glebovich gave the Tsar free rein to act against his now childless mother. It was easier to deal with a widow without heirs. The Morozov estate was entirely redistributed among the boyars or sold off. The nun Theodora was again taken to the Chudov Monastery, where, by the Tsar’s order, she was interrogated by Patriarch Pitirim (the Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus' following Nikon and Joachim II). The Patriarch spoke gently, trying to coax her into receiving Communion from him, but the confessor steadfastly refused. When persuasion failed, he attempted to force her, but she resisted even more fiercely. Frustrated, the Patriarch, "roaring like a bear," ordered the "convict" to be dragged down the stairs and returned to the Pskov Compound. This was done. Following Theodora, Evdokia and Maria were also interrogated by the Patriarch—with the same result.

After this, all three confessors were taken to the Zemsky Court, the "investigation bureau," where they were subjected to torture, resembling the sufferings of the early Christian martyrs. Their arms were twisted behind their backs and they were suspended in this position ("the rack"). They were threatened with fire and, half-naked, thrown into the snow. Then came flogging with whips, starting with Maria—first on her back, then on her stomach. Seeing Maria Danilova’s suffering and blood, Theodora wept and said to the torturers: "Is this your Christianity, that you should torment a human being so?"

During these days, the Tsar made a final attempt to negotiate with Theodora through an envoy, speaking to her gently: "Righteous mother, you are like the great martyr Catherine and shall be held in even greater honor if you do me this favor—at least outwardly show before everyone the ‘pinch,’ and then you may cross yourself however you wish." To this, Theodora replied: "I am not righteous, but a sinner, and the Tsar wrongly compares me, unworthy as I am, to a great martyr. But keep me, O Jesus Christ, Son of God, from placing upon myself the seal of the Antichrist."

Hearing her reply, the Tsar ordered Theodora to be transferred to the Novodevichy Convent, farther away, with instructions to prevent her from receiving any necessary supplies. However, this had the opposite effect: wealthy noblewomen who came to pray before the icon of the Smolensk Hodigitria would make it a point to visit the renowned boyarynya-confessor. The monastery courtyard became crowded with luxurious carriages. Even the Tsar’s elder sister, Irina, objected: "Why do you torment a widow by dragging her from place to place? This is not right, brother!" The Tsar, in response to his sister’s remark, issued an order for Boyarynya Morozova’s final exile, along with the two other confessors, Evdokia and Maria, to Borovsk, to a fortress, and into an earthen prison.

Upon entering the underground prison, Theodora found another nun already confined there, named Justina. It was here that the four sufferers were destined to complete their glorious struggle. Their lives ebbed away slowly amid hunger, cold, rats, and lice. At first, the guards secretly provided them with food, but when their superiors discovered this, they severely punished the violators, and conditions grew even worse.

After the feast of St. Peter in 1675, Fedor Kuzmishchev, a clerk of the Musketeer Office, arrived in Borovsk to investigate visits and offerings to the martyrs. By his order, Justina was interrogated. When she refused to fold her fingers in the three-fingered sign, she was burned alive in a log enclosure. The remaining sufferers were moved to an even deeper and darker dungeon, while Maria was transferred to another prison among hardened criminals. The guards were threatened with execution if they allowed anyone to approach the imprisoned women.

The first to depart to the Lord was Saint Evdokia. Before her death, she asked Theodora to join her in a service for the departure of her soul. After the prayers were sung, Evdokia "yielded her spirit into the hands of the Lord" on the 11th day of September. After Evdokia’s passing, Maria was returned to the earthen prison. The Tsar made one final attempt to soften the heart of Boyarynya Theodora, hoping that Evdokia’s death might have some effect. He sent an elderly monk to Borovsk to admonish her. However, upon seeing the chains binding Theodora and Maria, the monk himself wept and encouraged the saints to stand firm until the end, for the end was clearly drawing near.

On her final day, Theodora asked a guard to give her a small piece of bread. He replied that he could not, fearing the death penalty. She then asked him to wash her shift, saying that her death was near, and handed it to him. He fulfilled her request.

Theodora reposed in peace, in the depths of her dungeon, on the night of November 1–2, 1675. That same night, the elder Melania, who was far away in the wilderness, had a vision in her sleep of Theodora clothed in the great angelic habit, joyfully looking around her, and kissing the Cross and the icon of the Savior with gladness. Finally, in December, Maria also departed to the Lord, "and the third ascended to join the two, to rejoice eternally in Christ Jesus, our Lord."

The bodies of Evdokia and Theodora were buried in the same fortress. After 1682, their brothers, the Sokolnins, placed a gravestone over the burial site of the sisters. On the stone, they inscribed:

"In the year 7184 [1675], on this spot were buried, on the 11th day of September, the wife of Boyar Prince Peter Semenovich Urusov, Princess Evdokia Prokopyevna, and, on the 2nd day of November, the wife of Boyar Gleb Ivanovich Morozov, Boyarynya Theodosia Prokopyevna, in monasticism the nun-schemamonk Theodora. Both were daughters of Okolnichy Prokopy Fyodorovich Sokolnin. This stone was placed upon their graves by their brothers, Boyar Fyodor Prokopyevich and Okolnichy Alexei Prokopyevich Sokolnins."