The Oratorical (Rhetorical) Gesture in Icons: Not to Be Confused with the Gesture of Blessing

Modern iconography has not only forgotten the meaning and function of finger formation, but it the case of the “blessing” gesture, even corrupted it. I may at some point post an article about the New Rite blessing gesture being an image of the initials of the Saviour, but with yesterday’s homily on the feast of Ss. Peter and Paul by the 16th century St. Maximus the Greek (which was too long for Substack to send in an email), there is enough polemic to last a while…

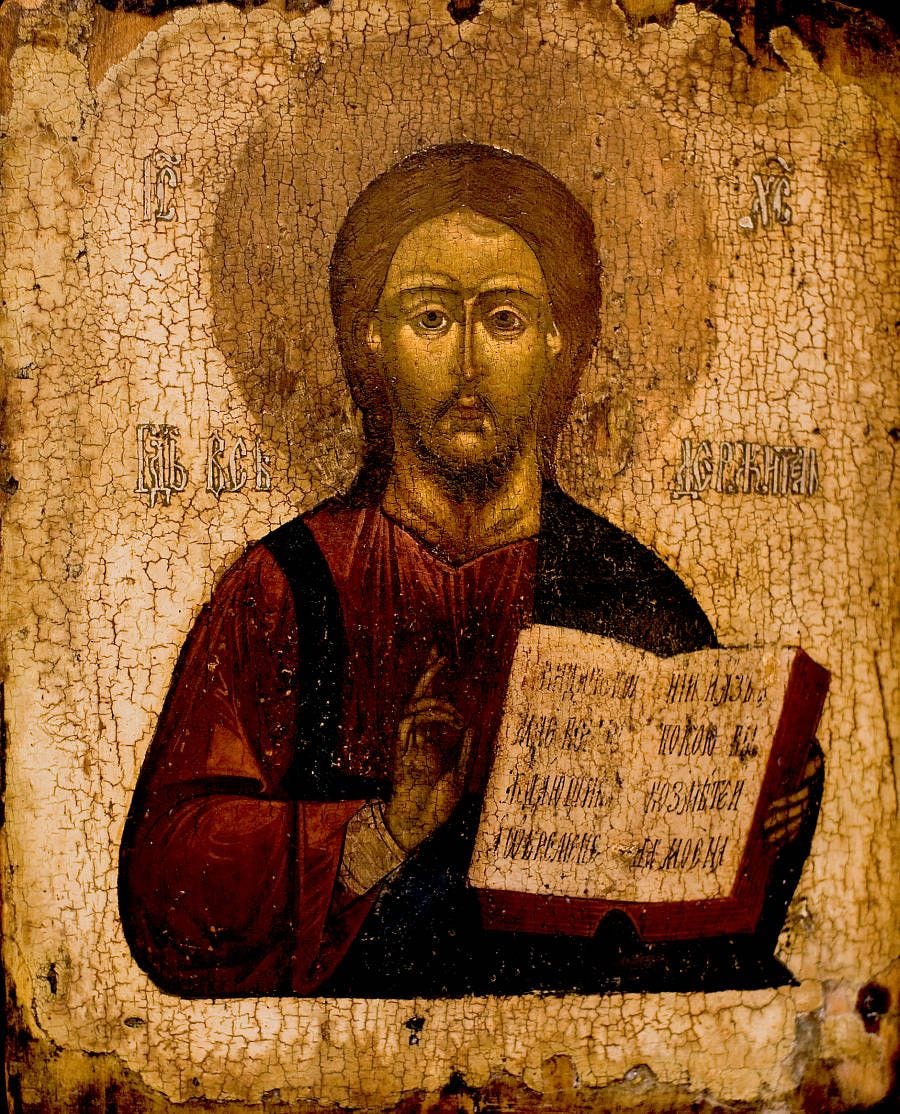

This oratorical gesture is mentioned in ancient treatises on the art of rhetoric. Therefore, from the earliest times, it has been frequently used in Christian depictions to indicate preaching, prophecy, and similar themes. Most often, it is accompanied by the image of the Gospel or a scroll in the hands of the depicted figure. For example, Archangel Gabriel is often shown making this gesture in the scene of the Annunciation, illustrating his address to the Virgin Mary with the famous words: "Rejoice, O Highly Favored One, the Lord is with thee." Note that Old Testament prophets are depicted with this gesture, as they could neither make the sign of the cross nor bless in the manner of saints.

However, St. Germanus of Constantinople (8th century) in his commentary on the liturgy notes that after the reading of the Gospel, the bishop makes the sign over the people with his fingers arranged in a similar composition. Remarkably, this is specified to be done after the Gospel reading, indicating that the finger gesture symbolizes the Gospel preaching. St. Germanus interprets this gesture not as denoting the name of Jesus Christ but in a much more intricate manner.

To consider the various finger arrangements found in ancient Christian iconography, it is relevant to list the types of finger gestures known to us as common rhetorical gestures.

Quintilian describes such a gesture: "The little finger and the middle finger are joined (bent under the thumb), while the other three fingers are extended (from the two middle fingers, the little finger is naturally middle); Quintilian states that this gesture is the most commonly used, suitable at the beginning of a speech, and in the continuation of the narrative, denunciations, and accusations." (Golubinsky)

Images of Christ and the saints, traditionally called “blessing”, do not actually carry that meaning and originate from ancient depictions of orators and philosophers. The ancients loved to accompany their words with gestures; pagan orators and philosophers, before delivering any speech or expounding their teachings, usually resorted to a variety of body movements, as if greeting their listeners or drawing their attention. At a dinner party hosted by a noblewoman, Hypatia Burrea, one of the guests, according to Apuleius, began his story by arranging the carpet around him, raising himself slightly on his elbow, lifting his right hand, and skillfully forming a gesture by bending the last two fingers to the palm and keeping the others free, following the example of orators. It is quite common to encounter images with this or similar gestures in ancient paintings and sculptures. In ancient paintings, this gesture is often complemented by a scroll held by the orators, philosophers, or scholars, along with something like a box or basket (scrinium) at their feet, containing several books or scrolls. Just recall the numerous similar images found in the catacombs depicting Christ as a teacher, the apostles, and prophets as preachers, to be convinced of the close connection, if not identity, between these historical-symbolic subjects and their attributes with the conventional representations of orators and philosophers in classical painting and sculpture. Originating and growing on the ground imbued with the traditions of the ancient world, early Christian art, as well known now, utilized everything it could from classical art, from the common techniques to the complete adoption of ready-made artistic models. It did not neglect the conventional gestures of pagan orators and philosophers, adapting them to its own purposes and imbuing these foreign forms with new Christian content. (Golubtsov A.P. From Readings on Church Archaeology and Liturgy)

And here, it is worth reminding that Christian culture in general, and Christian iconography in particular, did not arise in a vacuum. It is, so to speak, a "creative reworking" of Hellenistic ancient culture. The gesture we are considering is no exception. It was borrowed from the ancient rhetorical tradition. Greek and Roman orators had their own set of gestures with which they accompanied their speeches.

The Roman rhetorician Marcus Fabius Quintilian writes most extensively about such gestures in his book "The Orator's Education". He discusses nine oratorical gestures, but we will select those that later became part of Christian iconography:

1. The ring finger is bent under the thumb, while the other fingers are extended forward. This gesture is characteristic of the beginning of a speech [like the phrase “Let us attend” -OB], as well as for narration, censure, or accusation.

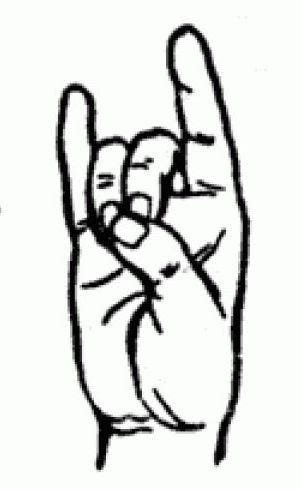

2. The middle two fingers are bent under the thumb, while the index finger and little finger are extended forward. This is an "urgent" gesture according to Quintilian.

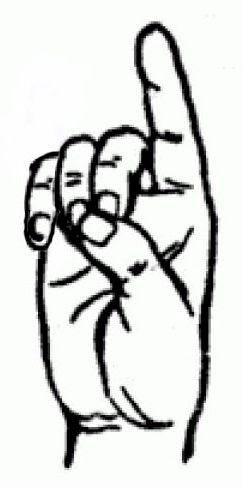

3. The last three fingers are bent under the thumb. The index finger is extended. This is a gesture of censure and indication.

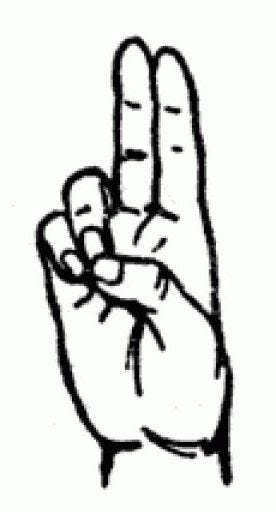

4. The thumb, ring finger, and little finger are bent. The index and middle fingers are extended.

In iconography, we see the same thing:

Thus, it can be summarized that similar gestures in icons generally imply direct speech of the character or a call to "heed," rather than a blessing in the sense of making the sign of the cross. This is also supported by Christian historical sources. For example, the Byzantine historian Paul the Silentiary in his description of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople mentions an altar veil on which the image of the Savior is woven, "extending the fingers of His right hand, as if speaking the ever-living word, and in His left hand holding a book that contains the divine words."

In this context, for example, the gesture of the Archangel Gabriel in the scene of the Annunciation does not mean blessing the God-bearer, but rather the good news (gospel) in the most literal sense of the word.

Of course, this does not mean that Christ cannot be depicted with a blessing gesture at all. It simply reiterates that any iconographic symbol should be "read" in its context.

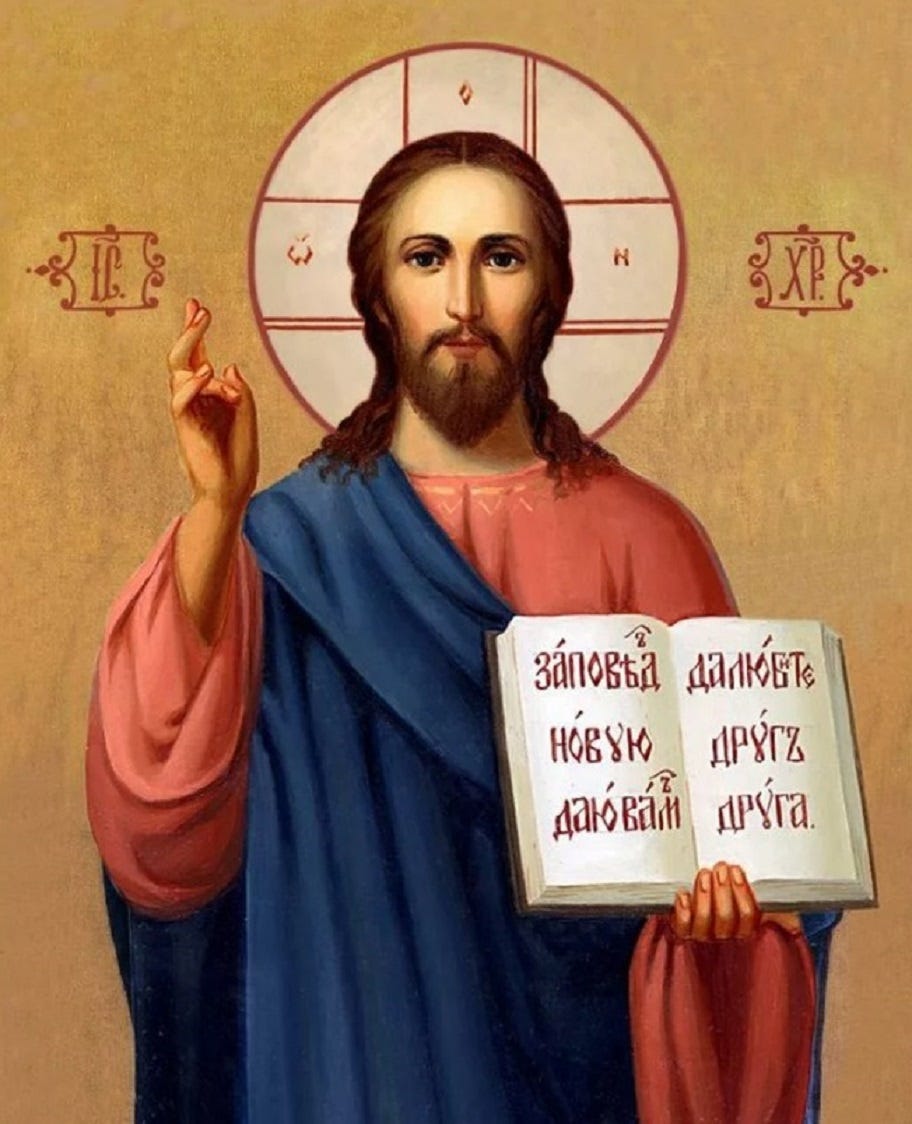

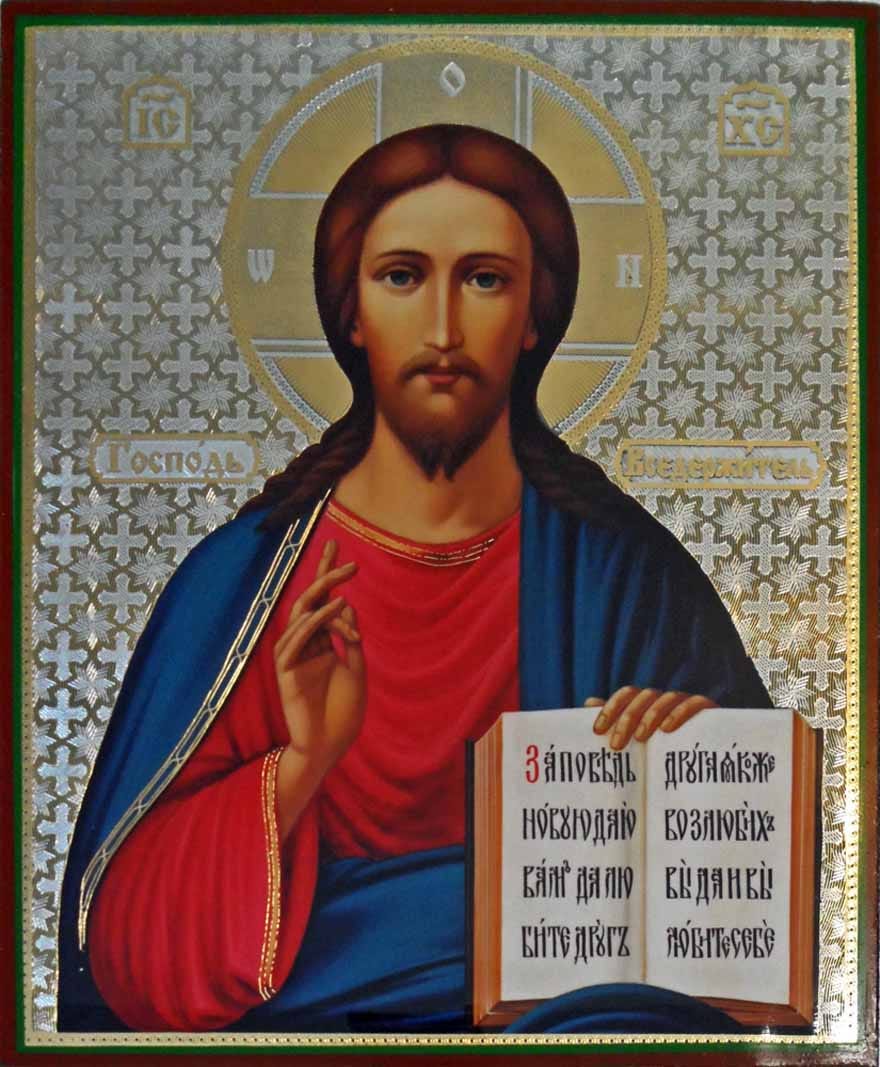

Unfortunately, after the Nikonian reforms, New-Rite iconographers in the subsequent centuries began to make increasing use of the raised little finger, which historically was the exception, not the rule, to the point that it is used almost exclusively now, going from this:

To this: