The Pomorian Answers

Below is an introduction from a modern Russian publication of the famous so-called “Pomorian Answers”, a book of responses to 106 official questions compelled upon a northern monastic settlement of Old Believers under the reign of Peter I. The responses have been one of the jewels of Old Believer history. This introduction gives not only important background on the book itself, but also an account of the Vyg settlement, called the “Vyg desert”, which holds an equally important cultural significance to Old Believers. An English Edition is being prepared.

Also, there is still time to sign-up for the online discussion group on the 1649 Small Catechism on September 21st. Both the English and Russian groups still have some open slots available…

…Do not remove the everlasting boundaries…(Prov. 22:28)

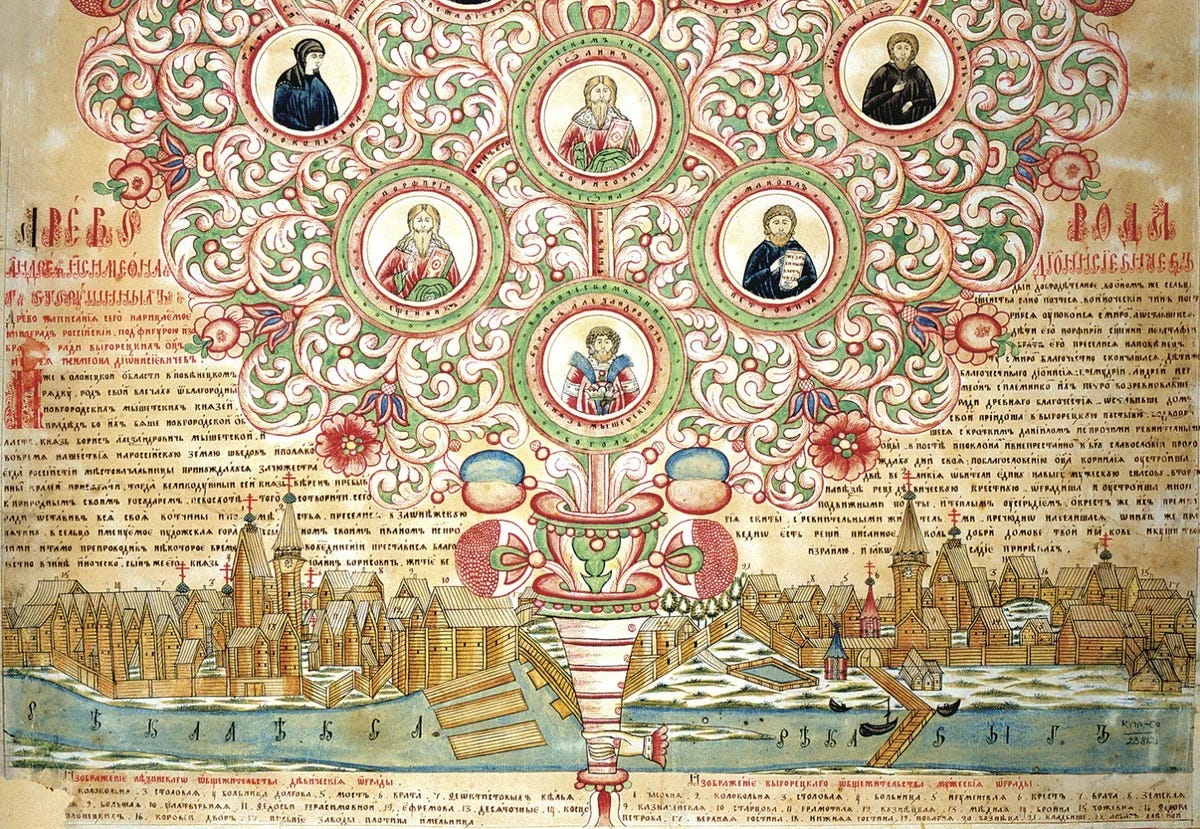

Concerning what the “Old Believer Vyg” is, a great deal has been written, and this Orthodox "republic" with its special self-governance has been sufficiently studied. The name of this monastery, located to the northeast of Lake Onega, was given by the Vyg River; there were no settlements here, only forests and swamps, with large cities far away. At the end of the seventeenth century, these places became a refuge for monks who refused to accept the Nikonian reforms, originating from northern Russian monasteries, particularly Solovetsky, and soon for numerous peasants who were developing the local lands. The Vyg communal brotherhood arose from the union of two settlements: one founded by Zakhar [Zacharia] Drovinin, the other by the former deacon Daniil Vikulin, who had previously lived in Shunga, and the townsman Andrei Denisov (1674–1730).

"When in 1702 Peter I with his army was traveling along the famous 'Tsar's Road,' laid through ancient forests and swamps from Nukhcha to Poventsa," writes E. M. Yukhimenko, citing the first historian of the Vyg Desert, Ivan Filippov, "fear gripped the entire Old Believer district: some prepared to suffer for the faith, others to abandon the already inhabited places. The Tsar was informed that Old Believer hermits lived nearby, but Peter, more occupied with the impending siege of Noteburg, replied: 'Let them live,' and 'passed peacefully.'" Soon thereafter, three years later, the Vyg settlement was assigned to the Poventsa ironworks and, along with official status, received freedom of creed and worship. Life in the desert was organized according to monastic rules. In 1706, twenty versts from the men's monastery on the Leksa River, a women's monastery arose, with Andrei Denisov's native sister Solomoniya as its first abbess.

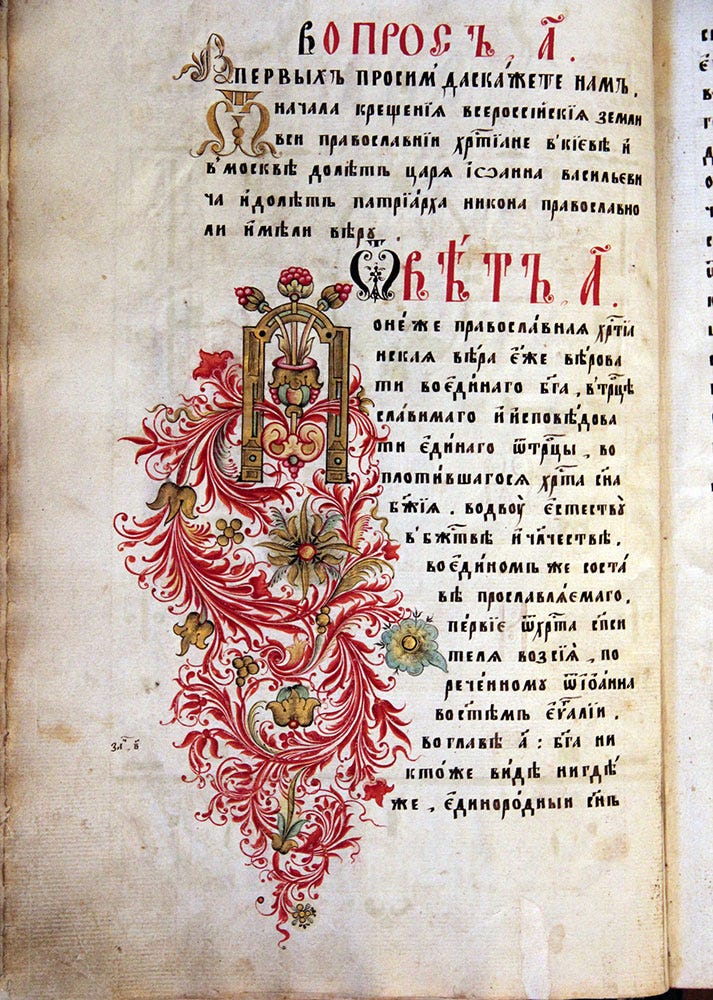

According to data from the mid-eighteenth century, the Vyg communal brotherhood owned 27 sketes and 12 plowmen's homesteads. These Pomor settlements became a significant industrial and cultural center of the Russian North. Here, on the Vyg, a vast school of book copyists emerged, writing in a special style known as Pomor script. Books were produced with extraordinary speed and distributed in large quantities throughout Russia. This "copying workshop" produced more books than the Moscow patriarchal printing house of that time, the only one in all of Russia.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Edinovery publicist V. G. Senatov, who openly sympathized with the Old Believers, wrote that "the works of the Denisov brothers and other Vyg Desert dwellers impress with the elegance of their style, the variety and depth of dogmatic, canonical, and church-historical knowledge, and understanding of human life. In literary and factual terms, they are no lower, if not higher, than the foremost writers of the dominant confession at that time, Theophan Prokopovich and Dimitri of Rostov. The so-called 'festal homilies' (sermons for feast days) of Andrei Denisov possess greater literary merits than the Chetii-Minei of Dimitri of Rostov. The school of the Vyg Monastery, as is now reliably known, stood higher in educational significance than the schools at episcopal residences of that era. The same can be said of other Old Believer schools."

The Vyg was secured by the purchase in 1710 at auction of arable land on the Chazhenka River in Kargopol district. "Upon reading the history of the Vyg Desert," V. G. Senatov continued, "from the first line to the last, one feels that enlightened people live and act here, easily giving precise accounts of their deeds and thoughts, energetically adapting to life in the cold, uninhabited, lifeless northern deserts. Skillfully and vigorously they master the vast region from Lake Onega to the White Sea and by sea to Vaigach. Under their hands, work boils everywhere and continuously: forests are cleared, fishing industries are established, huge stocks of timber float along lakes and rapids rivers, fishing vessels ply the lakes, rivers, and Arctic Ocean, making their way to Novaya Zemlya and almost to the mouths of the Ob. From these same people, large detachments of them constantly work on the Volga and its northern tributaries. For the needs of the north, they bring here huge caravans of grain from the queen of rivers. Andrei Denisov turned away from the newly founded Petersburg at that time and himself appeared there very rarely. In Petersburg, food supplies sometimes ran short, and then Andrei Denisov easily supplied the capital with fish from the north, from Lake Onega, and with whole caravans of grain from the Volga. This entire people, laboring in the sweat of their brow, everywhere—on rafts, on ships, morning and evening, at the appointed hours—perform the statutory orderly divine service. Each of the people spends their leisure time with a book. No gathering, for whatever reason it occurs, takes place without lively conversations on religious topics. Everywhere there is intensive work on studying the dogmas of the faith and statutory rites from old books... From here, books were distributed throughout Russia by whole wagonloads, sometimes openly, sometimes hidden in fish or grain."

In the year 1722, the learned hieromonk Neophyt, dispatched by the Synod, arrived at Vyg “for discourse concerning the ongoing ecclesiastical discord and for admonition.” He prepared a list of 106 questions, to which the Vyg community was required to provide answers, and accordingly, the same number of responses was produced. The primary work in preparing these was undertaken by Andrei Denisov, the cenobiarch of the Vyg communal brotherhood, an eminent Orthodox writer and apologist, already mentioned above. According to some accounts, he hailed from the impoverished princely family of Myshetsky, which had fallen into decline by the end of the seventeenth century. At the age of seventeen, he left home and spent an entire winter in the forests with a friend. In 1694, having met Daniil Vikulin, he co-founded the Vyg communal brotherhood, of which he was elected head by council on September 17, 1702, and remained in that role until his death. In addition to the Pomorian Answers, he authored around a hundred or more works, becoming one of the founders of the Vyg literary school.

Contemporary Old Believer authors highlight four distinctive features in Andrei Denisov’s views, as expressed in the Pomorian Answers. He believed that: 1) Russian Orthodoxy, that is, the complete fidelity to the faith of the holy apostles and all God-bearing fathers in the Russian Church before Patriarch Nikon, was perfect and unblemished; 2) Nikon’s reforms and the decisions of the councils of 1656 and 1666–1667 darkened the brilliance of Russian sanctity with superstition and the blindness of heresies; 3) the sacraments performed by the new-rite church lack true significance, and in particular, that baptism by pouring does not cleanse from original sin nor impart the grace of the Holy Spirit; 4) the same applies to the sacrament of the priesthood, which has ceased in the dominant church, though it formally exists; 5) yet Russian Old Believer priestless communities hold hope for the restoration of the priesthood among themselves, as true priesthood may still exist somewhere in the universe and is preserved until the end of the world.

In the Pomorian Answers, a paleographic (as it is now termed in scholarship) analysis was conducted for the first time on forgeries produced under Peter I—namely, the so-called Conciliar Act against the Heretic Martin and the Theognost Service Book. With these, supporters of Nikon’s reforms sought to entrench their ritual innovations. The conclusions of the Vyg scribes have been confirmed centuries later by modern researchers: “In our time, the Conciliar Act and the Service Book of Metropolitan Theognost have become classic examples of the falsification of written historical sources in Russian history. Indeed, they stand at the origins of deliberate forgeries with a clearly expressed ideological purpose, bear many characteristics typical of fabrications, and are remarkable for the history of their reception in public consciousness. The story of the Conciliar Act and the Service Book of Metropolitan Theognost eloquently demonstrates that, with regard to forgeries, truth inevitably triumphs. Scholarship always prevails in disputes with scholasticism, deceit, and hypocrisy, no matter how arduous the path to publicizing the truth.”

The responses to Neophyt were composed in two copies, with the work completed in the summer of 1723. One copy was submitted to the chancery of the Petrovsky factories in Olonets, and the second was handed to the hieromonk himself, the author of the questions. Andrei Denisov’s closest assistant was his brother Semyon, along with many other Vyg residents who aided in searching for necessary information and books. Andrei Denisov considered the effort in preparing the responses a collective one.

As previously mentioned, Hieromonk Neophyt arrived at Vyg by order of Peter I, who, in his decree of April 22, 1722, demanded to “immediately send to the Old Believers residing in Olonets district, from the Synod, a spiritual person for discourse concerning the ongoing ecclesiastical discord and for admonition.” Neophyt arrived at Vyg in late September, and in early December of that year, through a clerk accompanied by a soldier, he delivered the 106 questions to the Vyg Desert dwellers. By his order, the Vyg community was obliged to appear before him at the Petrovsky factories for “discourse” (in modern terms, a debate). All of this is mentioned in the Pomorian Answers. On September 4 and 5, 1723, after the submission of the responses, a public discussion took place between Neophyt and the Vyg fathers. They were released in peace, with each side maintaining its position. Neophyt forwarded the received responses to the Synod and, shortly thereafter, unexpectedly died at the Petrovsky factories, failing to fully complete his “admonitory” mission. Meanwhile, the Pomorian Answers began to circulate throughout Russia.

“Reading these writings,” writes V. G. Senatov (including about the Pomorian Answers), “one feels that their authors transcended both rhetoric and scholastic tendencies. The beginnings of education in the Old Believer milieu did not remain in a crystallized form, as was the case in the schools of the dominant church. In a reworked form, they penetrated the very depths of the people’s spirit, becoming the possession not only of the school bench or the learned, but of the entire people, constantly stirring and engaging the people’s thought, touching more or less strongly the mind of every person, from youth to gray-haired elder, transforming a person’s entire life until the grave into a seat at the school bench. The movement of Old Believer enlightenment is composed of two factors: the constant reworking and reassessment of the foundations of education and their penetration into the very depths or core of popular life. In Old Belief, one cannot find a single teaching that does not reach the deepest layers of the people or that arises by chance, in a study or some equivalent thereof. There are no educated individuals here who do not live, with all their being, with all their strength, thoughts, and feelings, the life and thought of the people down to its smallest manifestations. Nor is there a teaching whose seeds are not sown among the people themselves.”

The Old Believer Vyg endured many trials throughout its history. It was devastated in the mid-1850s, its residents were evicted, and its chapels were ordered to be closed “by sealing,” with the inventoried property also subject to removal. Yet, even in the years that followed, a flicker of the old faith persisted here. With the ascension of Alexander II, many Vyg dwellers returned. The new tsar’s policy was marked by certain relaxations toward the Old Believers. However, Vyg was no longer the same; it had lost its economic and industrial significance. It could not gather the same number of inhabitants as in its years of prosperity, but it remained a spiritual center.

In the nineteenth century, the Pomorian Answers were first published by printing press in 1884 at the Manuilov Monastery (now in Romania) by the hieromonk Arseny (Shvetsov), later Bishop of the Urals. Regarding the original text that formed the basis of this book, Hieromonk Arseny noted in a brief introductory remark: “For this present edition, we have chosen their original redaction, borrowing for this purpose a copy from the library of the Belokrinitsa Metropolis, a very old copy, as indicated by an inscription made in another hand on the margin at the first Answer, stating: ‘These Answers are 88 years from this year 7309’—presumably contemporary with their composition. However, this copy of the chosen redaction is not the only one; we have seen others like it in Moscow in the Khudov library and in other private hands. Only in the copy from which we print are some leaves missing, and this deficiency we have supplemented from copies in the libraries of our monastery and the Iasi Dormition Church. In this, by the duty of true justice, we deemed ourselves obliged in places to add our own marginal notes, so that this excellent apology for ancient church traditions and rites should encounter no stumbling block from any quarter.” Subsequently, legally, in the early twentieth century, between 1911 and 1913, the Pomorian Answers were published by three printing houses: in Moscow, at the presses of G. K. Gorbunov and P. P. Ryabushinsky, and in Uralsk, at the press of A. V. Simakov. In 1995, they were reissued in a reprint by the Old Believers of the Tver Nikolskaya community (Belokrinitsa hierarchy, Moscow).

The period of the Russian church schism—a Russian national tragedy—is studied primarily from the perspective of the history of book culture, while Old Belief itself is often reduced to ethnography, folklore, and singing traditions. It is not studied as a distinct path of Russian Orthodoxy with its own philosophy and apologetics, spiritual quests and wanderings, or history, where immense significance was attached to the individual, the parish, the will of the church people, as a unique Russian experience of resisting evil through nonviolence, against our first “Europeanization.” Indeed, so it is. “O woe, woe, poor Russia! What has made thee crave German deeds and customs! And to Nikola [Nicholas] the Wonderworker, a German name: Nikolai,” (Protopope Avvakum).

The distinctiveness of the Pomorian Answers lies in their universality: they are recognized by all Old Believer agreements, both those with priests and those without. Some of their propositions, theses, and conclusions would find development in the subsequent works of Orthodox apologists; one might mention, for example, question 67 and its answer regarding the depiction of the two-part cross, a theme of the well-known Circular Epistle of I. G. Kabanov (Xenos)—and this is but one example. The Pomorian Answers are not an apology for the schism, which is crucial to understand. To say that this work is an apology for Old Belief is, in principle, correct, but more precisely, it is an apology for authentic Orthodoxy, its pre-Nikonian Russian tradition, and this monument of theological-apologetic thought merits thorough and widespread study.

-Viktor Bochenkov.

This introduction was taken from Bochenkov’s modern Russian translation of the book, which can be purchased, in Russia, here.

I also look forward to the English translation of this book. All of your translations have been marvellous. You have a good thing going in that department.

I appreciate that! I know, of course, that my opinions on Origen may scandalize, and I humbly ask forgiveness for that. But I would also remind those curious, that his commentaries were widely read and utilized long after his death. He was deeply admired by the Cappadocian fathers, and Bl. Jerome literally plagiarized him. As to his condemnation, it is debatable that it even happened - but the manner in which the 5th Ecumenical Council occurred, and how its decisions were forced, is far more consistent with Nikonianism and its approach than anything the Old Believers uphold or was seen in the other Ecumenical Councils. It was certainly very far from any sense of "Sobornost" as a free expression of the voice of the Christian Church. I am a very strong advocate for his reconsideration today. But, this is absolutely my personal view alone.