Can one not be Orthodox and simply believe in God in their soul?

It is quite common to hear statements like this: “I am Orthodox, baptized, but I don’t go to church. I don’t trust priests. But I believe in God in my soul. I wear a cross. I’ve been taught not to steal or wish harm on others. I believe that’s enough. After all, the main thing is to live with God in your soul.”

Such faith has nothing to do with Orthodoxy. To be Orthodox, certain conditions must be met. One must be part of the Church and a specific community, regularly attend services (not just once a year at Pascha or Theophany), participate in the Sacraments (especially Confession and Communion), observe fasts, pray at home, know the Holy Scriptures, and strive to fulfill Christ’s commandments, among other things. After all, as the Apostle James writes, “Even the devils also believe and tremble” (James 2:19). For instance, if you expect to receive a salary, you must go to work, not just be listed as an employee. If you haven’t shown up to work for a week, a month, or two without a valid reason, and then find out you’ve been fired, no amount of arguing with HR or showing your employment record will make a difference. No one will listen to you.

What does “faith in the soul” mean? What is implied by this phrase? Faith “in the soul” suggests something buried deep down—so deep that it’s out of sight. What do we push to the furthest shelf? Things we don’t need. Items we use regularly are kept close, but those we don’t need are tucked away. We don’t throw them out because we might need them someday, but for now, they’re out of the way. It’s the same with “faith in the soul.” For such a person, faith only gets in the way of real life. True faith, however, manifests itself in actions.

If you consider yourself a believer, can you recall the moment when you came to faith in God, in Christ? Faith doesn’t come by birth. What event made faith take root in your soul—a sermon, reading Scripture, a divine miracle, or a conversation with someone? If there was no faith, and then it appeared, such a change is impossible to overlook.

What changes occurred in your life after faith appeared? Faith should bring a profound transformation in the soul. Coming to believe in Christ, a person reevaluates their entire life, repenting of past sinful deeds. The Savior is needed only by those who feel they are perishing. If someone thinks everything is fine, they won’t feel the need for a Savior. As the Apostle Paul writes:

“Examine yourselves, whether ye be in the faith; prove your own selves” (2 Corinthians 13:5).

Christ said:

“Except your righteousness shall exceed the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 5:20).

“The kingdom of heaven suffereth violence, and the violent take it by force” (Matthew 11:12).

A useful criterion to determine if you have even a little genuine faith is this: Recall the last time you wanted to harm someone—a neighbor, colleague, or supervisor—but refrained, not because you couldn’t, but because you remembered that God forbids it, and so you stopped. If you struggle to recall such a situation, it may mean you don’t yet have faith.

— Priest Yevgeny Gureyev

What was the cause of the schism in the Russian Church in the 17th century?

The schism began with Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov’s desire to reform the Russian Church through Patriarch Nikon, modeling it on contemporary Greek and Ukrainian practices.

The 17th-century reforms affected not just a narrow circle of specialists but every member of the Church. They touched upon familiar and deeply ingrained elements: the sign of the cross, the name of the Savior, the Creed, and well-known prayers and books, such as the Psalter.

The real objectives of the reform were not ecclesiastical but political. The goal was not so much to eliminate or correct errors in church books—something the Russian people largely agreed with—but to change and unify all the rites and customs of the Russian Church according to the models of the Greek and Little Russian (Ukrainian) Churches. Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich was captivated by the idea of becoming the ruler of all the Orthodox in the East, akin to the Byzantine emperors.

At that time, neither the Greeks nor the Ukrainians had independent states. The Greeks were under Turkish rule, and the Ukrainians were under the Poles. For these groups to seamlessly integrate into a unified state, it was necessary to ensure that no significant differences existed between their church traditions and those of the Russian Church. However, the unification was carried out not according to Russian Church traditions but based on those who had been under the influence of heretics. Naturally, this sparked protests within Russian society. The Greek Church had signed the Union of Florence with the Catholics in 1439, and a similar union was concluded at Brest-Litovsk in 1596. Since then, anyone from these territories, whether clergy or lay refugees, fell under suspicion regarding the purity of their faith. After the Time of Troubles in the early 17th century, a series of anti-Latin councils were held in Moscow. The baptismal practices of immigrants from Ukraine and Belarus (whether by immersion or sprinkling) and Greek prayers were scrutinized. Only after such checks were Greek and Little Russian clergy allowed to serve in the Russian Church. During this period, the idea of “Moscow as the Third Rome” took hold: “Two Romes have fallen, and a fourth shall not be.” The Russian Church bore the burden of safeguarding the purity of Orthodoxy. Now, however, there was a proposal to change everything in the Russian Church according to the practices of those the Russians themselves had previously scrutinized for orthodoxy.

But that was not all. Following the reform, it was not enough to adopt questionable practices; it was also necessary to anathematize all the rites and customs of the Russian Church as heretical. The reformers claimed that everything in the Russian Church was wrong, alleging that our forefathers did not know how to pray, make the sign of the cross, or even pronounce the name of God correctly. The very idea of the Third Rome was rejected. Everything, down to the smallest details, now had to be done as the Greeks did—those who had recently come to Moscow as beggars now became teachers of the Church. The same applied to Ukraine, where throughout the 18th century, only Ukrainians were appointed as bishops. Naturally, those with a shred of conscience who were unafraid of persecution stood against this "reform," which was essentially the execution of the Russian Church. As the holy martyr Archpriest Avvakum said:

"They have plundered my Mother Church, and should I remain silent?"

— Holy Martyr Archpriest Avvakum

As a result, a resistance movement arose against the destruction of the Russian Church, and its participants faced severe persecution. When it was impossible to silence all dissenters, they were declared schismatics and state criminals. Thus, the schism in the Russian Church came to pass.

— Priest Yevgeny Gureyev

When did the two-finger sign of the cross and the veneration of the eight-pointed cross originate?

The sign of the cross is a "hidden apostolic tradition," as stated by St. Maximus the Greek. We believe that from the very beginning, the sign of the cross took the form of the two-finger gesture (dvoeperstie), as affirmed by Orthodox Church Fathers, including Blessed Theodoret, Bishop of Cyrus; St. Peter of Damascus, hieromartyr and confessor; St. Maximus the Greek; the Holy Fathers of the Stoglavy Sobor (Hundred-Chapter Council); and the Orthodox Greeks who composed the "Rite of Reception from the Jacobite Heresy," where the origin of the two-finger sign of the cross is attributed to Christ Himself:

“Εἴ τις οὑ σφραγίζει τοῖς δυσὶ δακτύλοις, καθὼς ὁ Χριστός, ἀνάθεμα”

This is translated into Church Slavonic as:

“Иже кто не знаменается двема персты, яко же и Христос, да будет проклят”

"Whosoever does not sign themselves with two fingers, as Christ did, let them be anathema."

— Stoglavy Sobor, Chapter 31

This is also confirmed by external writers, such as the Greek canonist Nicodemus the Hagiorite, who notes that in his 91st Canon, St. Basil the Great speaks of the apostolic origin of the two-finger sign of the cross. Let us examine the canon and its commentary:

"Canon 91. Of the dogmas and teachings preserved by the Church, some are outlined in the Scriptures, while others are passed down to us from apostolic tradition in secrecy. Both are of equal significance for piety, and no one, even slightly familiar with ecclesiastical rules, will dispute this. Indeed, if we were to reject unwritten customs as insignificant, we would unwittingly distort the Gospel itself and render the preaching void. For example (I will first mention the most ordinary and common), who taught through Scripture that those who place their hope in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ should sign themselves with the sign of the cross?"

St. Basil goes on to list other traditions: praying facing east, the Eucharistic rite, and triple immersion in baptism, among others. Nicodemus the Hagiorite comments:

"The ancient Christians arranged their fingers differently [from modern Greeks] when making the sign of the cross, using only two fingers—the middle and index fingers—as described by St. Peter of Damascus (Philokalia, p. 642). According to him, the entire hand represents the one hypostasis of Christ, and the two fingers symbolize His two natures."

— Nicodemus the Hagiorite, Pedalion: The Canons of the Orthodox Church, Vol. 4, Yekaterinburg, 2019, pp. 188, 194

Notably, this book is a “recommended publication” by the Moscow Patriarchate's Publishing Council, which does not itself adhere to the two-finger tradition.

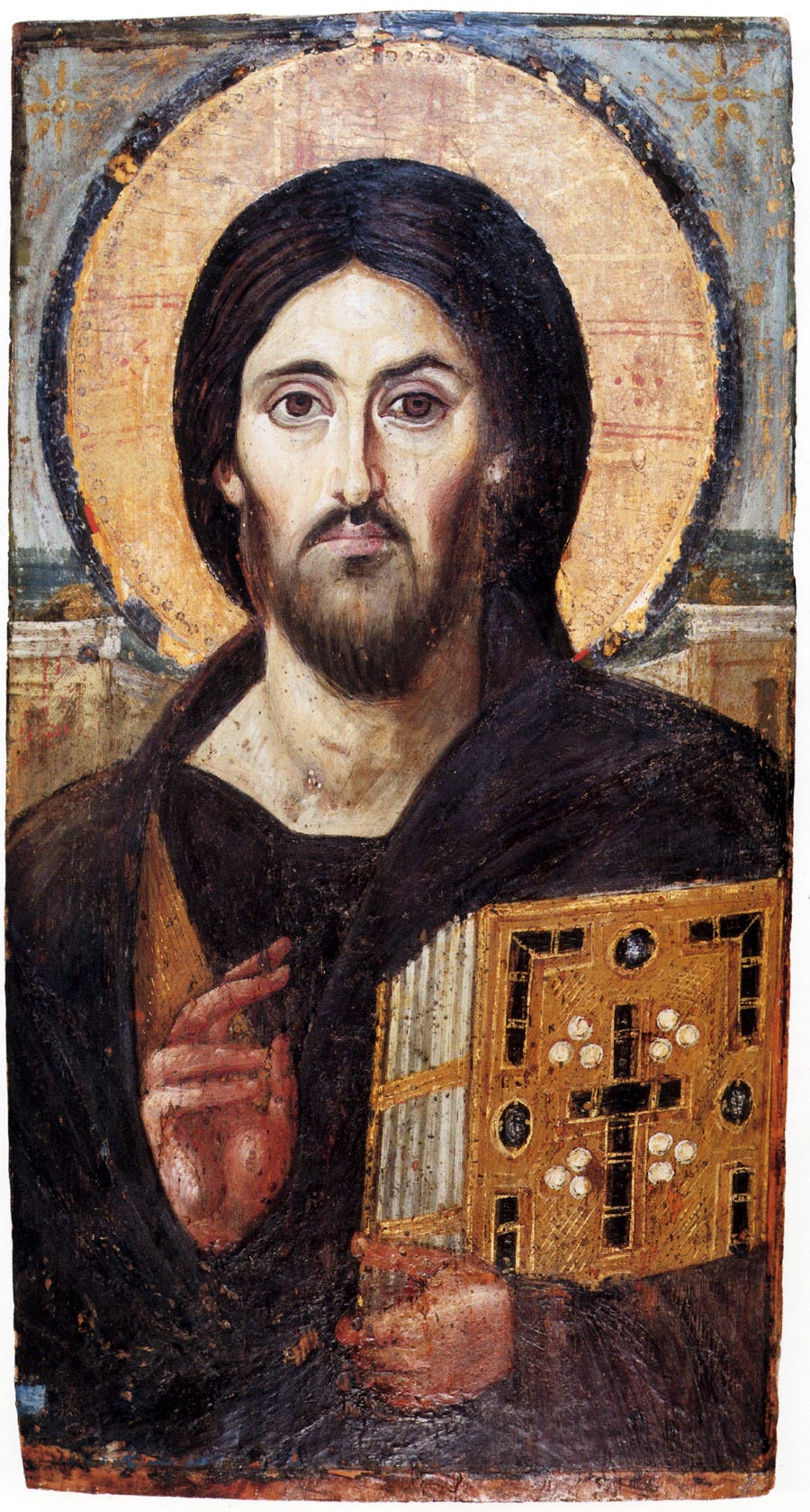

Comparing the Apostolic Creed with the symbolism of the two-finger sign of the cross, one finds that nearly everything in the Creed is reflected in this gesture: belief in the One God in three Persons (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit), Christ's Incarnation (His two natures in one hypostasis), His birth from the Virgin, His crucifixion, resurrection, ascension to the right hand of the Father, and His future Second Coming to judge the living and the dead. Thus, when a Christian makes the two-finger sign of the cross, they visually confess the Apostolic Creed—the oldest version of the Creed. This provides further evidence of the apostolic origin of the two-finger sign of the cross. Moreover, countless artifacts of early Christian art attest to this form, as detailed in the book by S.I. Bystrov, The Two-Finger Gesture in Monuments of Christian Art and Literature, which compiles material evidence of the two-finger gesture from the early Christian era in the Roman catacombs to the Old Ritualist Schism.

For example, the sixth-century icon of Christ from the Sinai Monastery (above), preserved without later alterations, clearly depicts the ancient two-finger gesture.

The Cross of Christ is venerated by Christians as the Altar on which our Lord offered Himself for our salvation. References to the veneration of the cross can be found as early as the epistles of St. Paul. The apostolic sign of the cross is nothing less than a symbolic depiction of the Cross on one's body.

Christians have depicted the cross in various forms: as the letter "T," an equal-armed cross (still seen on liturgical vestments), a six-pointed cross (where the upper bar symbolizes the "titulus" of Pilate), and a seven- or eight-pointed cross (with the lower bar symbolizing the "footrest"). By the end of the first millennium after Christ's Nativity, the eight-pointed form (historically the most complete representation of the Cross) became the most widespread in both the Christian East and West. Among Orthodox Christians, it gradually replaced the six-pointed cross. The Stoglavy Sobor of 1551 established the rule that the domes of churches should be topped with eight-pointed crosses (Stoglavy Sobor, Chapter 41, Question 8).

Orthodox Old Believers venerate the three-barred Cross of Christ as a great holy object but do not condemn other historical forms of the cross, including the four-pointed cross, which serves as a foreshadowing of Christ's sacrifice found in the Old Testament. The pectoral crosses of the Old Believers often take the form of a four-pointed cross with the Golgotha cross (eight-pointed) embedded within.

— Archpriest Vadim Korovin

What icons are canonical, and which are non-canonical? What should be done with non-canonical icons acquired before joining the Old Believer faith that are very dear to one’s heart?

The ancient canons of the Orthodox Church do not strictly regulate the forms, types, techniques, or materials used to create sacred images, except for specific prohibitions. For instance, the 82nd Canon of the Sixth Ecumenical Council forbids depicting Christ as a lamb, and the Stoglavy Sobor (Chapter 41-1) commands that icons be painted "according to the ancient models, as the Greek iconographers painted, and as Andrei Rublev and other renowned iconographers painted." It specifies that they should follow the ancient examples and not be based on "one's own imagination" (Stoglavy Sobor, Chapter 43). Therefore, it is not permissible to paint icons using live models or in a style that is non-iconographic and more secular or worldly. Additionally, the Holy Fathers prohibited using fragile, short-lived materials for icons, as such negligence can lead to the sacred image deteriorating easily, which demonstrates a lack of reverence for the work of God. This negligence is condemned in Scripture (see Jeremiah 48:10).

Moreover, Christians should not pray before images of individuals recognized as saints not by the true Church but by heretical groups.

If you have an icon of a "non-saintly saint," meaning someone canonized by non-Orthodox rather than Old Believer Orthodox Christians, it is best to return it to those who venerate it—namely, the heretical group.

If you possess an icon of a saint venerated in our Church but painted "not according to the model," meaning in an unorthodox style, you should do the same—return it to the community from which it originated. In extreme cases, if these icons are "dear to your heart," you could, after consulting with your spiritual father, keep them at home as mere decorative paintings, not as icons for prayer. However, I would recommend not clinging to personal habits or attachments that weaken the soul but instead fostering strictness in spiritual life rather than emotional sentimentality. From this perspective, it is better not to keep such images at home at all.

In any case, this matter should be resolved with the advice and blessing of your spiritual father.

— Archpriest Vadim Korovin

How does one correctly transition from the New Rite Church to the Old Rite Church? What is the process, what should one know, and from which sins (such as smoking) should one abstain?

The answer to this question largely depends on the individual’s specific life circumstances. It is one thing if the person is relatively healthy, young, and not in immediate danger of death, meaning they likely have time for a thorough preparation before joining. It is another matter entirely if the person is gravely ill, physically weak, elderly, or facing imminent danger, such as a risky surgery or military deployment, or another threat of death. In such cases, the process of joining should not be delayed for an extended period.

In the first case, where "time is not pressing," it is recommended to undergo a period of catechesis before joining. During this period, one should study the faith, the history of the Church, strive to live according to Christ’s commandments, and renounce smoking, drunkenness, fornication, and other habitual mortal sins. One should also demonstrate a period of abstinence from such defilements to confirm genuine repentance and reform. This catechetical period may last 40 days (a traditional ancient practice) or even longer—several years if necessary—depending on the individual’s readiness. The duration is determined by the priest overseeing the person’s transition. St. Justin Martyr writes that during catechesis, the candidate must renounce pagan customs, especially offering sacrifices to idols; if they do not, baptism cannot be performed.

According to the Great Potrebnik, the catechumen is to meet with the priest weekly—specifically after Vespers on Thursday—to report on their spiritual progress and receive special prayers. Unfortunately, in modern practice, priests often do not require this of catechumens.

The rite of joining the Church varies depending on the person’s prior baptism and the community in which it was performed (if any). If someone was baptized in a heretical community of the 2nd or 3rd rank, where the baptism was performed by a heretical priest in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit with three full immersions in water, they are not re-immersed but are received through repentance and renunciation of heresy, followed by either chrismation (2nd rank) or purifying prayers (3rd rank).

If the person was not baptized with three full immersions in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, or if they come from a heresy of the 1st rank, they are received through renunciation of heresy and full baptism.

In emergency cases, such as an imminent danger of death, the catechetical period is shortened to the utmost degree, and the person is received into the Church immediately following the catechesis. The priest has the authority to adjust the catechetical period according to the specific circumstances, always prioritizing the spiritual benefit of the person seeking to join the Church.

— Archpriest Vadim Korovin

Are there saints among the Old Believers after the Schism?

In Christ's Church, saints are always present in every generation of Christians. Propagandists from among the New Rite often accuse the Old Rite Orthodox Church of lacking saints after the Schism. This is a profound misconception. Some of the more honest historians of the New Rite Church acknowledge that the number of canonized saints within the New Rite Church sharply declined following the Schism. For instance, G.P. Fedotov, in his book Saints of Ancient Rus, wrote:

"The primary path of Moscow piety directly led to the Old Belief... With the Schism, a significant, though narrow, religious strength departed from the Russian Church."

He further speaks of "the deadening of Russian [New Rite] life, whose soul has departed." By "departed soul," he refers to holy people. Thus, according to G.P. Fedotov, "for the past centuries of the Russian [New Rite] Church, one can study the history of spiritual life and the history of righteousness, but not yet the history of sanctity."

During the period of New Rite dominance after the Schism, about which Fedotov states there was "zero sanctity in the last quarter of the 17th century," the Old Rite Orthodox Church saw a shining host of martyrs, confessors, ascetics, and righteous ones. These include not only the fiery Archpriest Avvakum, burned at the stake for his faith, and the noblewoman Feodosia Morozova (Nun Feodora, venerable martyr), starved to death in an underground prison, but also many others. Saints have continued to arise in the Church throughout subsequent centuries, though sadly, many remain unknown to most.

Here is a list of just some of the Old Believer saints after the Schism:

Hieromartyr Pavel, Bishop of Kolomna and Kashira (+1656).

Hieromartyr Daniil, Protopriest of Kostroma (+c. 1653).

Venerable Leonid of Ustneduma (+1654).

Venerable Bogolep, youth of Chernoyar (+1654).

Confessor Loggin, Protopriest of Murom (+1654).

Venerable Eleazar of Anzersk (+1656).

Venerable Ilya, first Archimandrite of Solovki (+1659).

Venerable Eufrosin of Kurzhensk (+early 1660s).

Venerable Spiridon Potyomkin (+1665).

Martyrs Feodor, fool-for-Christ, and Luka, wonderworkers of Mezen (+1670).

Venerable Martyr Avraamy (in the world, Afanasy), fool-for-Christ (+1672).

Martyr Kiprian Nagoi, fool-for-Christ (+1675).

Venerable Martyr Iustina (+1675).

Martyrs Princess Evdokia Urusova and Maria (+1675).

Martyr Isaiah of Moscow (+before 1676).

Venerable Martyr Feodor the Singer, of Moscow (+before 1676).

Venerable Martyrs Nikanor Archimandrite and Monk Makary, Martyr Samuil Sotnik, and 400 monks and lay brothers martyred in the Solovki Monastery (+1676).

Venerable Arseny of Kerzhensk (+no earlier than 1676).

Martyr Ioann Ulyanin (+1679).

Martyrs of Kargopol: Andrei and his daughter Glykerya, Nikita and his wife Neonila, Ioann, and Afanasy (+1679).

Venerable Martyr Eleazar of Olonets (+1679).

Olonets Martyrs Alexander Guttoev, Gavriil Korelyanin, and Mark Olonchanin (+1679).

Martyrs Ierofei, Evdokia, and Natalia of Olonets (+1679).

Martyr Grigory, farmer of Olonets (+1679).

Venerable Iov of Lgov, new wonderworker (+1681).

Hieromartyr Protopriest Nikita Dobrynin (+1682).

Hieromartyr Lazar, priest of Romanov (+1682).

Martyr Deacon Feodor (+1682).

Venerable Martyr Epiphany of Solovki (+1682).

14 Martyrs of Novgorod: Nobleman Dmitry Khvostov with his sisters Matrona and Paraskovia, their two handmaids, Vasily, Tit, and others (+late 17th century).

Martyr Sampson, son of a Novgorod priest (+late 17th century).

Venerable Martyr Ioasaf of Kirilov (+late 17th century).

Martyrs Evdokim and Grigory of Charonda (+late 17th century).

Venerable Isidor of Kerzhensk (+after 1670).

Hieromartyr Simeon of Tobolsk, priest (+late 17th century).

Venerable Dosifey, Abbot of Chirsk (+c. 1690).

Venerable Kirill of Sunaretsk (+1690).

Venerable Korniliy and Vitaliy of Vyg (+early 1690s).

Martyr Feodor Tokmachev (+1694).

Venerable Ioasaf of Vetka (+1695).

Venerable Dalmat, Hermit of Isetsk (+1697).

Venerable Sofoniya of Kerzhensk (+c. 1700).

Venerable Feodosiy of Vetka (+1710–1711).

Venerable Martyr Deacon Alexander of Kerzhensk (+1720).

Venerable Iov of Tagil (+1741).

Venerable Iakov of Tagil (+after 1742).

Venerable Lavrenty of Vetka, founder of the Starodub Michael Archangel Monastery (+1776).

Venerable Maksim of Tagil (+1783).

Venerable Isaakiy and Ioasaf of Irgiz (+late 18th century).

Venerable Iona of Kerzhensk (+c. 1819).

Venerable Pavel and Alimpiy of Belaya Krinitsa (+1854, late 19th century).

Venerable Martyrs Arkady and Konstantin, wonderworkers of Shamara (+1857).

Confessor Ambrosiy, Metropolitan of Belaya Krinitsa (+1863).

This is far from a complete list of God's saints who shone forth in the Russian Orthodox Old Believer Church after the Nikonian Schism.

For those wishing to learn more about the lives of some of these saints, I recommend my book This Generation Shall Not Pass, published in Moscow in 2022. A download link is available here.

— Archpriest Vadim Korovin

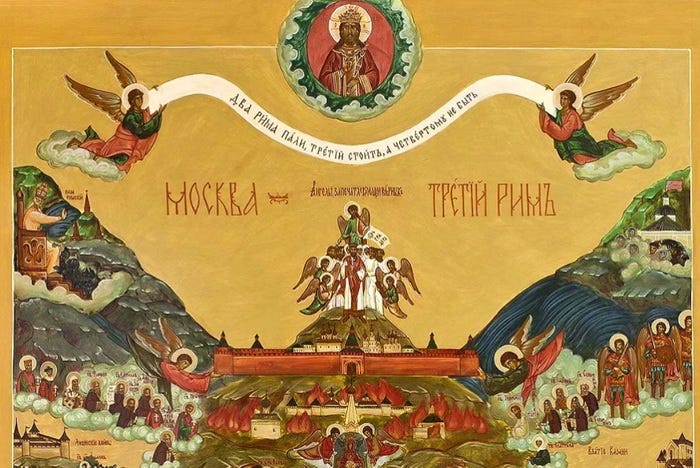

What is the meaning of the concept "Moscow is the Third Rome, and a fourth there shall not be"? Are Russians somehow special or better than others?

The medieval Russian concept was slightly different and more comprehensive in its original form. Its essence can be summarized as follows: the First Rome, the Orthodox kingdom, fell into heresy; the Second Rome (Constantinople) fell to the Turks; now the last Orthodox kingdom is Moscow, the "Third Rome." If Moscow were to fall, there would never be a "Fourth Rome." Thus, the Russian kingdom bears the greatest responsibility for preserving the true faith in a fallen world. If it were to fall into heresy or be conquered by nonbelievers, it would result in a universal spiritual catastrophe, a prelude to the coming of the Antichrist.

This concept does not imply that Russians are "better than everyone else." There is no trace of "Russian chauvinism" in it. Instead, it places a heavy burden of responsibility on Russian Orthodox Christians to preserve the purity of faith on earth, akin to what is expressed in the Apocalypse of St. John the Theologian:

"Thou hast a little strength, and hast kept My word, and hast not denied My name... Behold, I come quickly: hold that fast which thou hast, that no man take thy crown."

(Revelation 3:7–11)

Spiritually, this is precisely how our Orthodox ancestors understood the phrase "Moscow is the Third Rome, and a fourth there shall not be" before the Nikonian Schism: "Hold fast till I come" (Revelation 2:25). However, by the mid-17th century, the ruling circles in Russia replaced this spiritual understanding with a purely earthly interpretation. They pursued the idea of creating a vast Eastern empire under the Russian Tsar, uniting Greeks, Serbs, Bulgarians (to be liberated from the Ottoman Empire), and other Orthodox peoples under their rule. The ambition of placing a "cross over Hagia Sophia in Constantinople" captivated the minds of secular rulers for centuries. In striving for this mirage, they were willing to sacrifice the purity of Orthodox faith—destroying the spiritual "Third Rome" to construct its earthly counterfeit. The purity of Orthodoxy had already been abandoned by those nations they sought to annex. The plan involved reforming the Russian Church to match the practices of other nations, facilitating their painless integration into the new empire and Church.

This hidden yet most significant cause of the 17th-century Church reform ultimately led to a complete failure for the reformers. They not only failed to liberate the aforementioned peoples from the Turks or unite them with Russia, but they also failed to achieve uniformity in worship. Instead, faithful Russian Christians, adherents to the ancient Church Tradition, were executed, tortured, persecuted, exiled, and imprisoned.

Nevertheless, the Orthodox Old Believer Church, despite all persecutions and hardships, withstood this trial. To this day, it remains the spiritual continuation of the "Third Rome," which was dismantled in the mid-17th century—not as an earthly human kingdom, but as a kind of embassy of the Kingdom of God on earth. The doors of this spiritual embassy remain open to all who seek Truth and Salvation, regardless of their racial or ethnic origin.

— Archpriest Vadim Korovin

What is spiritual kinship? How can couples in the Old Believer tradition avoid becoming spiritual relatives before marriage?

Spiritual kinship, often referred to as "kinship through the cross," typically arises through baptism, when godparents are appointed for the baptized individual. A spiritual kinship exists between the godfather (or godmother) and their godchild, equated by Church rules to the relationship between a biological parent and child. The Sixth Ecumenical Council, in its 53rd canon, states that spiritual kinship is even greater than physical kinship.

Accordingly, the Church established a prohibition on marriages between a godfather and goddaughter, a godmother and godson, as well as their descendants up to the eighth degree of kinship1.

This kinship is considered "in a direct descending line" from the godparent and godchild: their children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and so on.

Additionally, godparenthood (kumovstvo) constitutes spiritual kinship. For example, a godfather cannot marry the mother of his godson or goddaughter, and a godmother cannot marry the father of her godson or goddaughter. Furthermore, if a man and woman are godparents to the same godchild, they also share spiritual kinship (as "kumm" and "kumma" to one another), preventing them from entering into marriage.

Those who share the same godparent are also considered spiritual relatives (godbrothers or godsisters) and are forbidden to marry each other, as are their descendants (up to the eighth degree of kinship).

Since a child's grandparents are direct ancestors in the ascending line, they should not serve as the godparents of their grandchild. Otherwise, this creates kinship ties between the parents of the child, as the son or daughter of a godparent cannot be married to the "kumm" or "kumma" of their parent.

To avoid such non-canonical situations, spiritual kinship between those entering into marriage and their direct ancestors should be examined. When selecting godparents, care must be taken to ensure that they do not create kinship ties among the baptized child's parents. It is most practical to appoint relatives of the baptized child from the collateral line (e.g., uncles, aunts, cousins). Collateral kinship does not result in spiritual kinship through baptism.

Additionally, spiritual kinship includes cases of ecclesiastical adoption of a child (through the "Rite of Adoption," see the Great Potrebnik) or brotherhood (through the "Rite of Brotherhood," which is no longer practiced). In such cases, the relationship between the adoptive parent and the adopted child is equivalent to that of a biological parent and child, with all its consequences. This means that the adoptive parent and adopted child, as well as their descendants, cannot marry each other (up to the eighth degree of kinship in their lineage).

— Archpriest Vadim Korovin

Does the Church have any requirements or recommendations regarding a Christian’s health?

In Orthodoxy, there is no strict dichotomy between the soul and the body, nor any teaching that all physical things are sinful and corrupt, with the soul’s ultimate goal being to escape the "filthy" body. Orthodox Christianity teaches that the body and soul together form a single human being and that Christians living on earth, in their bodies, are temples of the Spirit who dwells within them (1 Corinthians 3:16).

Orthodox teaching warns against all forms of bodily excess and impurity, including gluttony, drunkenness, fornication, and adultery. These vices are known to cause severe physical and mental illnesses.

The Church prohibits smoking tobacco and the use of intoxicating drugs. Abortions are strictly condemned in Orthodoxy, considered deliberate infanticide, regardless of the method by which they are performed.

The Church also forbids mutilating surgeries such as castration, equating them with murder, including voluntary castration (without medical necessity). This prohibition extends to so-called "gender reassignment surgeries," a trend artificially promoted in the West.

Tattoos on the body are forbidden as well. It is also known that tattoos carry an increased risk of cancer.

One of the most important Orthodox practices is observing the fasts: weekly one-day fasts (Wednesdays and Fridays, the Exaltation of the Cross, and the Beheading of John the Baptist) and multi-day fasts (Great Lent, the Apostles’ Fast, the Dormition Fast, and the Nativity Fast). During fasting days, the soul is cleansed from sins through repentance and asceticism, and the body is lightened from dietary excess, contributing to its health.

The Church strictly prohibits seeking healing from sorcerers or fortune-tellers, as their "help" is based on interactions with humanity's enemies—the fallen spirits, "spirits of wickedness in high places." These spirits cannot provide true healing but, in exchange for temporary visible improvements in health, separate a person’s soul from God and lead them to spiritual ruin unless they repent and return to God.

At the same time, seeking help from doctors is both permissible and encouraged. Scripture portrays the physician as a servant of God through whom the Lord grants relief from illness and healing:

"Honor a physician with the honor due unto him for the uses which ye may have of him: for the Lord hath created him. For of the Most High cometh healing, and he shall receive honor of the king. The skill of the physician shall lift up his head: and in the sight of great men he shall be in admiration. The Lord hath created medicines out of the earth; and he that is wise will not abhor them. Was not the water made sweet with wood, that the virtue thereof might be known? And he hath given men skill, that he might be honored in his marvelous works. With such doth he heal men, and taketh away their pains. Of such doth the apothecary make a confection; and of his works there is no end; and from him is peace over all the earth. My son, in thy sickness be not negligent: but pray unto the Lord, and he will make thee whole. Leave off from sin, and order thine hands aright, and cleanse thy heart from all wickedness... Give place to the physician, for the Lord hath created him: let him not go from thee, for thou hast need of him."

(Sirach 38:1–11)

In severe illnesses, we must also remember the Holy Mysteries given for the healing of both soul and body: confession, unction (anointing), and communion of the Body and Blood of Christ. Since some illnesses are permitted as a consequence of our sins, purification from sin can lead to healing. The Mystery of Unction, in particular, grants forgiveness of all sins, including those forgotten in confession, and can aid in recovery.

Ultimately, the complete deliverance from all bodily ailments and death awaits us in the future Resurrection and the renewal of all creation by God.

— Archpriest Vadim Korovin

Hello who doesn't know where he's coming from. Does not know where he is heading to. This is very important to know history and the teachings of the church . It as well helps us to build our faith stronger. I love it only the burden is to spread the massage to the young generation.God bless the works of your hands and wide you wisdom.