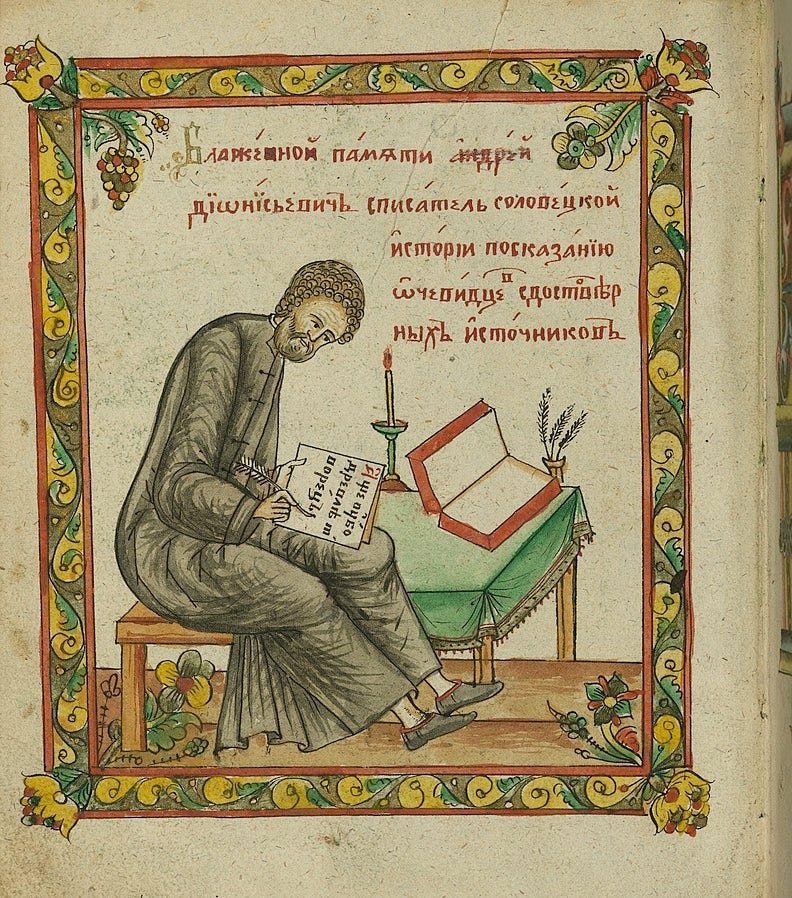

Andrey Denisov and His Contribution to Old Believer Scholarship and Enlightenment

by Roman Atorin

The study of sources related to the Russian schism reveals that the confessional policy of the Russian Empire toward the Old Believers was far from tolerant. In 1722, Emperor Peter I issued a special decree mandating a policy of "coercive missionary work" by the state Church to bring the residents of the Vyg Old Believer community into the fold of official Orthodoxy. That same year, a missionary group led by the Synodal hieromonk Neophytos was sent to Pomorye. They prepared 106 catechetical and polemical questions for the Old Believers to respond to. The painstaking effort of the Vyg Old Believers resulted in the publication of the Pomorian Answers in 1723. While this work is considered a collaborative effort, Andrey Denisov, the leader (kinoviarch) of the Vyg communal monastery, played the central role in its authorship.

Denisov was the first in Russian scholarship to apply the paleographic method to his research. Possessing a sharp intellect and extensive knowledge in history, philosophy, theology, and linguistics, he created a foundational theological treatise that defined the doctrinal principles of Russian Old Belief—ancient Orthodox dogmatics. The Pomorian Answers serve as a unique Old Believer catechism, a systematic and analytical work unparalleled in the history of Old Believer thought. This achievement demonstrates Denisov’s remarkable ability to address abstract questions of doctrine and ritual with erudition. It is no exaggeration to say that the Pomorian Answers were the first Russian scholarly treatise written according to rigorous academic methods.

The style of the Pomorian Answers is marked by the complete absence of the polemical subjectivity sometimes found in the writings of early Old Believer leaders, such as Protopriests Avvakum and Ioann Neronov, or the well-known 20th-century Old Believer historian and theologian F.E. Melnikov. Within its pages, one does not find harsh attacks against the opposing confessional group. Denisov maintained a measured, polemical tone throughout the book, carefully analyzing contentious ecclesiastical issues step by step.

A central topic of contention between Old Believers and the post-Nikonian Church is the form of making the sign of the cross. Of the 106 questions posed by Hieromonk Neophytos, 26 responses in the Pomorian Answers are devoted to this issue, covering questions 5–15, 39–47, and 50 (parts 1–3).

At the outset of their study on the sign of the cross, the Vyg elders provide a general description and systematization of evidence regarding the two-fingered sign (dvoeperstie):

"Which fingers were used to make the sign of the cross, as adopted by Prince Vladimir from the holy Eastern Church, and how this was preserved by the entire Ancient Russian Orthodox Church, is shown by three reliable testimonies:

a) by custom, which remained uninterrupted until Nikon;

b) by holy icons, both Greek and Russian, displayed uniformly in all Russian churches;

c) by holy books, both handwritten and early printed, which testify to the same practice."

Denisov organizes the accumulated material into several categories:

Patristic writings supporting the correctness of the two-fingered sign;

The incorrupt relics of Russian saints who used this form of the sign of the cross, with their hands remaining positioned in the two-fingered posture;

Testimonies of the two-fingered sign in Orthodox iconography;

Confirmation of the two-fingered sign in doctrinal and liturgical texts.

Through extensive research, Denisov identified 105 archaeological and historical testimonies showing that the Russian Church did not know the three-fingered sign (troeperstie) before Patriarch Nikon. The Pomorian Answers significantly expand the scope of patristic statements on the sign of the cross, adding figures such as Blessed Theodoret of Cyrus, Peter of Damascus, Meletius of Antioch, and Maximus the Greek, as well as the anti-Catholic polemicist St. Nikephoros Panagiotis. Denisov extensively cites the works of these Church Fathers in his analysis.

The author of the Pomorian Answers organizes the available sources chronologically, dividing them into periods corresponding to the reigns of Moscow princes and tsars. The compilers of the Pomorian Answers list a number of saints glorified by the Russian Church whose relics were found incorrupt and whose hands were positioned in the two-fingered sign of the cross (dvoeperstie). Among them are St. Theodosius of the Kyiv Caves, Ilya of Murom, and Joseph the Much-Suffering. Additionally, the compilers enumerate numerous Orthodox icons painted before the 17th century, on which the saints are consistently depicted holding their fingers in the two-fingered posture.

The book proceeds to analyze written doctrinal sources, which possess an ontological status as sacred texts and affirm the authenticity of the two-fingered sign of the cross.

After listing, reviewing, and interpreting the sources, the compilers draw the following conclusions:

Through such numerous testimonies, it becomes evident that Ancient Russian and Eastern Orthodoxy used the two-fingered sign, not the three-fingered one, for making the sign of the cross. Thus… all of Russia received this practice from the Eastern Churches and maintained it until the time of Patriarch Nikon, crossing themselves and blessing with two fingers.

The authors express confidence that the two-fingered sign was once the most widespread and universally accepted form of making the sign of the cross, with an ecumenical reach. However, by the time of Patriarch Nikon's reforms, the two-fingered sign had been preserved solely within the Russian Church.

To promote the three-fingered sign (troeperstie) among the faithful, the post-schism official Orthodox Church resorted to distorting historical facts. As a result, in the early 18th century, works such as Acts Against the Heretic Martin the Monk and Theophan’s Service Book (Feognostov trebnik) were published.

The authorship of Acts Against the Heretic Martin the Monk is attributed to Metropolitan Stefan Yavorsky, who introduced this document as a powerful tool in anti-Old Believer polemics. The Acts were essentially an appendix to Metropolitan Pitirim’s Spiritual Sling, a work aimed at refuting Old Belief.

Martin the Monk is a fictitious historical figure. According to the Acts, he allegedly arrived in Rus’ in 1149 and preached a dubious doctrine that blended Latin and Armenian theological positions. The Acts claim that the custom of the two-fingered sign, along with other church practices defended by the Old Believers, was introduced to Rus’ by this heretic. His teachings were supposedly condemned by a Kyiv Council in 1157.

When compiling the Pomorian Answers, the Denisov brothers (Andrey and Simeon) analyzed the Acts through historical and philological methods and concluded that the document was fraudulent, with the events it described being purely fictitious. They summarized the forgery’s glaring flaws as follows:

Unverifiable Existence of Martin: There is no reliable evidence for the existence of the heretic Martin or the councils allegedly convened against him, as no such references appear in any chronicles.

Chronological Inconsistencies: The timeline presented in the parchment document does not align with Russian chronicles or the reign of Prince Rostislav.

Discrepancies Between Versions: Later rediscovered and printed versions of the Acts differ significantly from Pitirim’s earlier version, with discrepancies in dates and omissions of many phrases.

Linguistic Anachronisms: The style of writing, customary expressions, and phrasing do not reflect the 12th century but instead resemble the conventions of the 18th century.

Bias in Content: The intent of the Acts seems less focused on Martin’s supposed heresies and more directed at opposing contemporary Old Believers.

Contradictions with Ancient Practices: The teachings described in the Acts contradict both Greek and Russian ecclesiastical traditions.

The Denisovs highlight these six points to expose the Acts as a forgery.

The Pomorian Answers demonstrate that the forgery by representatives of the dominant church was of poor quality. The Vyg elders found no historically authoritative or reliable evidence for the document in chronicles or ecclesiastical literature. Russian chroniclers and Greek historians do not mention a Kyiv Council in 1157 during the reign of Prince Rostislav and Metropolitan Constantine, nor do they record the supposed acts or doctrinal rulings of this council.

The Denisov brothers also point out the striking differences between the style and language of the Acts and the conventions of Old Russian writing. Critics noted that the Acts were written in a dialect closely resembling 18th-century speech rather than the language of the 12th century. Additionally, the document puzzled the scholars of the Vyg Desert community because neither Patriarch Nikon, nor Joachim, nor the early advocates of reform ever referenced Acts Against the Heretic Martin the Monk in their writings.

Through rigorous scholarly methods, the Pomorian Answers successfully debunked the forgery created by the Synodal Church. Nevertheless, references to the Acts continued to appear, even in the works of prominent historians of the Russian Church, such as Metropolitan Makarius Bulgakov, a member of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences.

The next stage in Andrey Denisov’s scholarly work was the refutation of the historical authenticity of the so-called Theophan’s Service Book (Feognostov Trebnik), a liturgical book attributed to Metropolitan Theophan. This forgery, also created by representatives of the state church, sought to assert the existence of the three-fingered sign of the cross (troeperstie) in Rus’ before Patriarch Nikon. The Pomorian Answers present compelling evidence that the Theophan’s Service Book is just as fraudulent as the Acts Against the Heretic Martin the Monk. This evidence is summarized in three points:

Contradictions with Earlier Metropolitan Writings:

Russian metropolitans such as Cyprian, Photius, Daniel, Macarius, and Patriarch Philaret wrote epistles on the sign of the cross and other liturgical practices that contradict the contents of this service book. "Had this Service Book existed, they would not have written in contradiction to it." Furthermore, during the reforms, Patriarchs Nikon, Joachim, and Joasaph never referenced this book, which convinced the Old Believers of its absence.Linguistic Anachronisms:

Linguistic analysis reveals inconsistencies with pre-schism Russian literary traditions. "The expressions and phrases are inconsistent with the conventions of Theophan’s time." The Pomorian Answers devote approximately three pages to analyzing these linguistic discrepancies.Discrepancy with Orthodox Tradition and Apostolic Spirit:

The service book’s inclusion of numerous anathemas against the two-fingered sign deeply troubled the authors. They argue that such condemnations could not have been written during Metropolitan Theophan’s time when the two-fingered sign was the widely accepted form for expressing Orthodox dogma in the Russian Church.

Thus, both the Acts Against the Heretic Martin the Monk and the Theophan’s Service Book were declared forgeries by the Pomorian Old Believer apologists, who highlighted the poor quality of these falsifications. The Vyg elders uncovered numerous glaring contradictions and inconsistencies with ancient Orthodox Apostolic tradition. "And since in both these books—the synodal Acts and the Theophan’s Service Book—so many doubts and contradictions with all teachers and the ancient Orthodox Church are found, we cannot trust them, and we greatly fear their deceitfulness," the authors conclude in their scientific verdict regarding the validity of the post-reformers’ arguments for the three-fingered sign.

Continuing their critique of the three-fingered sign as presented in Metropolitan Pitirim’s Spiritual Sling, the Pomorian Answers address the impossibility of the two-fingered sign having existed in the Latin Church, contrary to Pitirim’s claim. Pitirim cites the words of the Church Father Constantine Panagiotis in a conversation with a Catholic representative, urging him to adopt the three-fingered sign. However, Denisov demonstrates the evident absence of the two-fingered sign in Western Christianity. The words of St. Constantine, according to the Pomorian Answers, were misinterpreted by Pitirim to support his argument.

The Pomorian Answers also refute, based on archaeological evidence, the practice of five-fingered blessings (pyatiperstnoe imenoslovnoe blagoslovenie), which Pitirim claims to have been depicted on certain icons. The Vyg Old Believers, after examining the artistic heritage of ancient Russian iconography, find no examples of such blessings on icons and consider it a recent innovation. "Of all the icons in the Russian Tsardom, in cities, villages, and monasteries—be they Greek, Serbian, Bulgarian, or other ancient churches—all these depict the two-fingered posture for prayer and blessing, as we have extensively shown in Answer 5."

From a theological perspective, Denisov most convincingly argues for the heretical nature of the three-fingered sign, asserting its inadmissibility in the prayerful practice of an Orthodox Christian. He provides a clear dogmatic foundation for the defense of the two-fingered sign, which, according to the authors of the Pomorian Answers, is theologically complete and expresses the fullness of Orthodox teaching for the following reasons:

The ancient Orthodox Church teaches, through the two-fingered posture, the confession of Christ’s two natures in one hypostasis.

The two fingers symbolically express the confession of the God-Man crucified on the cross.

The three-fingered sign, promoted by the post-reform church, cannot convey such theological depth and instead introduces doctrinal confusion into the prayer life of believers. The act of making the sign of the cross, which symbolizes the cross during prayer, is meant to remind the faithful of the Crucified Christ, who bore the sins of the world. According to Orthodox teaching, it was Christ who was crucified on the cross, not the entire Holy Trinity, as the three-fingered sign implies. "For it was the One who took flesh from the pure blood of the Holy Virgin who accomplished all for our salvation and was crucified in the flesh, but His divinity did not suffer. For these blessed reasons, we confidently hold to the two-fingered sign of the cross, while we fear to adopt the three-fingered sign."

The accusation by synodal theologians that the two-fingered sign represents Arianism or Macedonianism—on the grounds that the Holy Trinity is depicted "unequally by the fingers"—is deemed by the Pomorian Answers to be an artificial and theologically baseless claim. They assert that Holy Tradition imparts the ancient sign of the cross with its true Orthodox meaning, consistent with Divine Revelation: "This confession bears no resemblance to the heresy of Arius. Arius taught three separate natures in the Trinity, proclaiming different substances for the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. He claimed the Son was created, not begotten, and that the Holy Spirit was a creation, not God. The Holy Church, in the arrangement of the fingers, teaches the confession of one essence, one power, and one honor in the Holy Trinity, which opposes Arian heresy."

Regarding Pitirim’s criticism that the Old Believers allegedly sin by depicting the Trinity "with three unequal fingers," the Vyg elders respond that the mystery of the Trinity cannot be fully articulated, especially through such rationalist analogies as catechetical explanations based on human anatomy. This type of theological reasoning, they argue, is alien to the Patristic tradition and Holy Tradition. The form of the sign of the cross, according to the Pomorian Old Believers, is a unified, symbolic, and complete expression of Orthodox dogma, with the two-fingered posture being the most accurate visual representation of Orthodox truths:

"And in the arrangement of the fingers (thumb, ring, and little finger, in the form of the two-fingered sign… the Church does not speculate about intermediaries… but declares the Hypostatic Trinity… the mystery of the Holy Trinity is expressed."

The accusation that defenders of the two-fingered sign are guilty of "Armenian heresy"—Monophysitism—is also theologically unfounded. "The ancient Orthodox Church, through the arrangement of the two fingers, confesses Christ’s two natures, opposing, not resembling, the Armenian heretics. The Armenians confess one nature in Christ and anathematize those who confess two natures, attributing suffering on the cross to His divinity. Yet, according to ancient printed books, those who cross themselves in opposition to the Armenians depict Christ’s two natures with the two fingers, symbolizing that Christ suffered on the cross in His flesh." Similar arguments are presented regarding accusations that the Old Believers’ sign of the cross is Nestorian.

The anathematizing of the ancient two-fingered sign and those who use it is seen by the Vyg Old Believers as an unprecedented and shocking event in church history: "Hearing of these curses and anathemas is terrifying for us, and to speak of them is dreadful and painful.”

Thus, the Pomorian Answers stand as one of the most theologically comprehensive and fully developed foundational texts of Old Believer apologetics. Within its pages is a systematic defense of church practices preserved by Old Believers, including the two-fingered sign. The significance of the Pomorian Answers remains relevant among Old Believers to this day. This monument of religious thought, born in the intellectual world of Russian Old Belief, may serve as a valuable source for studying the history of religious consciousness in Russia. A thorough scholarly analysis of the Pomorian Answers still awaits researchers, given the underexplored and widely relevant nature of this subject.

Thank you so much for this contribution. Now, it would be wonderful if the entire work were to be translated into English. There was a German language study created in 1957, titled, Die "Pomorskie Otvety" als Denskmal . . . by P.Johannes Chrysostomus, a Benedictine monk. It was only a commentary, not translation of the complete text.